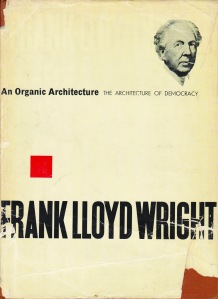

Lund Humphries Landmarks: An Organic Architecture by Frank Lloyd Wright (1939)

In May 1939, nearly 75 years ago, the celebrated American architect Frank Lloyd Wright visited London and gave four lectures at the RIBA. The meetings were hailed at the time as ‘perhaps the most remarkable events of recent architectural affairs in England. No architectural speaker in London has ever in living memory gathered such audiences.’

With great speed, the lectures appeared later that same year in book form, published verbatim under the title An Organic Architecture: The Architecture of Democracy by ‘Lund Humphries, London’, a firm whose name had up until then been associated with high-quality printing work and The Penrose Annual, a review of the graphic arts. So it was that in 1939, as democracy hung in the balance, the Lund Humphries publishing programme was launched with a book which set out to consider ‘the Place Architecture must have in Society if Democracy is to be realized’. Anthony Bell, who was to become Chairman of Lund Humphries, recalled being interrupted in his reading of the galley proofs in September 1939 by air-raid sirens calling him to ‘[march] out to the phoney war’.

Frank Lloyd Wright had been commissioned to give the lectures not by the RIBA itself but by the Sulgrave Manor Board, who funded the ‘Sir George Watson Chair of American History, Literature, Institutions’, established to promote and celebrate transatlantic cultural connections. From their inauguration in 1921 until 1939, courses of generally six Watson Chair lectures were given annually, alternately by eminent Americans and Britons. In his Foreword to the book, Frank Lloyd Wright makes clear that, because of the nature of the commission, ‘Strictly speaking these spontaneous talks were not intended to be “lectures” on Architecture’. His Afterword reiterates that ‘the Sulgrave Manor Board lectures should be concerned more with the place and character of architecture in modern life than in any way to practise it’. They provide a useful, if rather verbose, exposition of his core philosophy of organic architecture, with its aims of uniting form and function in a ‘new modern ideal’. Down with fashionable aesthetics! Form was to be determined ‘by way of the nature of materials, the nature of purpose’.

How did Lund Humphries come to publish the book in 1939? A key figure in the story was Eric (‘Peter’) Gregory, at that time joint Managing Director (with Eric Humphries) of Lund Humphries, who as well as being an early patron of English Modernist artists was also a friend and admirer of the architects of the time, including Jane Drew, Maxwell Fry and Wells Coates. Between 1938 and 1939, Lund Humphries published the journal Focus, founded as a mouthpiece for discontented architecture students at the Architectural Association, whose cause Gregory supported. Anthony Cox, co-editor of Focus and an ardent Modernist, had been involved in organising Frank Lloyd Wright’s visit and it is likely that he introduced the book project to Lund Humphries. Publication was a condition of the Watson Chair lectures, so the publishing costs of An Organic Architecture are likely to have been funded by the Sulgrave Manor Board.

Lund Humphries author Alan Powers, an expert on British Modernism, has been extremely helpful in clarifying the genesis and reception of An Organic Architecture. He says that the impact of An Organic Architecture on British architecture is hard to judge, but that the lectures caused a lot of comment, to which Wright responded in the RIBA Journal in 1939, claiming he had been misunderstood. ‘His influence acted more like a “sleeper”‘, Powers writes, ‘to resurface in the 1960s when the more rigid and normative formal language of Modernism began to break down, and there was a conscious reaction against man-made materials.’ The book itself was useful in disseminating the lecture texts, and included helpful black-and-white reproductions of Wright’s work, not readily available at that time. It clearly found a good audience, reprinting in 1941 and then again in 1970, and after the war would have been the most easily available book on Wright for British readers.

This is the first of a series of monthly posts on ‘Lund Humphries Landmarks’, each by a different author, which we will be publishing throughout 2014 in celebration of our 75th birthday. Over the coming months we will have Anthony Penrose on Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain under Fire (1941), David Mitchinson on the first edition of Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings (1944), Andrew Causey on Paul Nash (1948), Rick Poynor on Typographica (1949 to 1967), Sophie Bowness on Barbara Hepworth: Carvings and Drawing (1952), Ben Read on Ben Nicholson (1948 and 1956), Frances Spalding on William Scott: Paintings (1964), Peter Khoroche on Ivon Hitchens (1973), and John Hoole on The Last Romantics (1989).

In the meantime, do read Valerie Holman’s fascinating new history of Lund Humphries publishers, which is now live on our website together with a bibliography of our publications from 1939 to 2014. Happy 75th Birthday, Lund Humphries!

Lucy Myers, Managing Director