Architectural Tourism by Shelley Hornstein

Shelley Hornstein's new book, Architectural Tourism: Site-Seeing, Itineraries and Cultural Heritage, charts the relationship, and even the entanglement, between architecture and tourism. It reveals how architecture is always tied to its physical site, yet is transportable in our imagination – and into the virtual spheres of social media and armchair travel.

Read on for a teaser extract taken from the book's introduction...

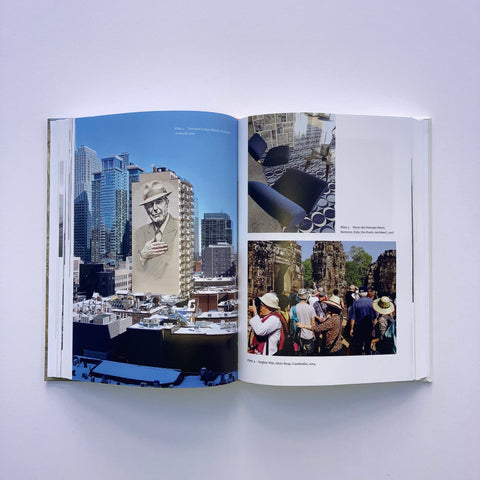

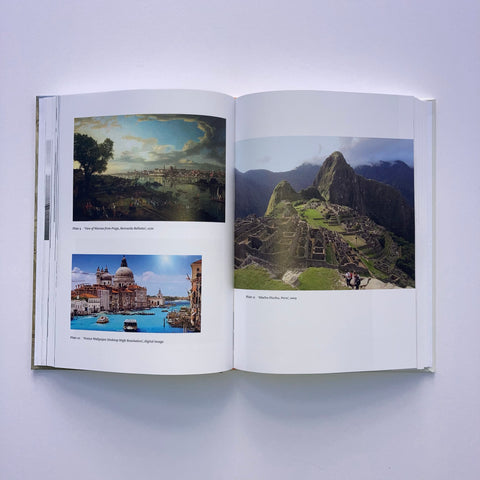

Around the world, architecture is a magnetic draw for tourists of all stripes. Since the era of pre-industrial religious pilgrimages, architecture has beckoned travellers. Religious and historic sights, or contemporary buildings designed by ‘star’ architects demonstrate that architecture has always been undeniably tied to our cultural and architectural heritage, our collective identity and perhaps above all, to the tourist industry. Think about what we remember about a city and why. Landmark buildings such as the Eiffel Tower in Paris by Gustave Eiffel or the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain by Frank Gehry, mark their place and leave an indelible memory for tourists. When we think of a place we’ve travelled to see, we usually think of the buildings or sites that linger in our memory. What is noticeably different today, and as a result of the indisputable impact the Bilbao museum has made, is that architects themselves have become celebrities. Therefore, while our identification of a place is often associated with the building and the cultural memory informed by it, now the name of the architect is a draw in itself.

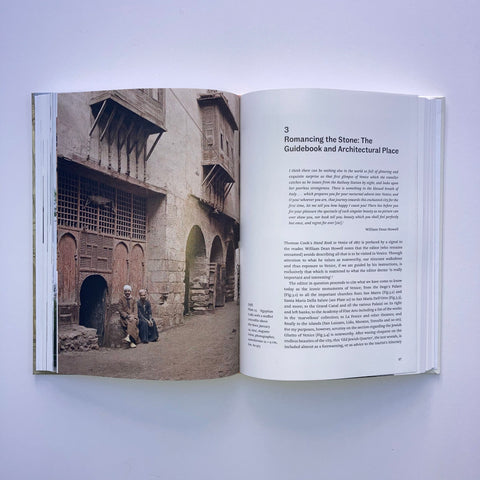

Architectural Tourism charts the relationship, and even the entanglement, between architecture and tourism. Key global icons of ‘spectacular’ architectural sites, such as the Eiffel Tower and the Taj Mahal, as well as key current ‘starchitecture’ iconic buildings beginning with the Bilbao Guggenheim are discussed, illustrating the manifold issues involved in architectural tourism. Buildings and places are used to ‘brand’ a city so that it is immediately recognisable in visual publicity. It is no coincidence that the major travel agencies such as Globus, Abercrombie & Kent, Carlson Wagonlit, or Expedia, flash images of iconic architectural sites on their website home pages. Travel is a quest of sorts: a quest for unearthing the foreign and the unfamiliar with the frisson that it might result in a mild, or even a rude, cultural awakening. A visit to the physical site is always paralleled today by digital and virtual cultural exploration across social media platforms on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook, to name but a few. Some travel is accomplished by not going anywhere at all – physically – but rather by way of the imagination through photographs, postcards, films, theatre, or literature. Illustrated by studies of international architectural icons, the book looks at how these buildings feature in literature, art and design, marketing and social media and reveals how the impact of these depictions combine to build up a deeply romanticised idea of the icon, which is central to the desire to visit it.

From the earliest recordings by Westerners of architectural ruins and the material cultural triumphs of past cultures to the continuing thirst for knowledge of architectural sites today, tourists yearn for a connection to built forms, a material connection to place, and a desire to know the world. The Romans admired the Greeks, the Italian Renaissance masters reconsidered Roman antiquities, the Enlightenment period was preoccupied with archaeological ruins, and colonising nations portrayed indigenous cultures with mythologised histories. Architecture and the places in which they are located are markers of culture and cultural consumption. Yet while travel to places and architectural discovery has been an activity told and documented for centuries, the democratisation of travel as mass tourism only really developed as a leisure activity during the 19th century. Since then, tourists move in greater numbers from a familiar place (home) to a faraway place, and then return to the point of departure. The 19th century afforded a kaleidoscopic vision of the world that was mediated by the then current technologies: trains, steamships, and cameras. Each of these recorded and ‘captured’ movement and the new spaces of modernity. Suddenly the world became two dimensional, seen through the lens of the camera or panoramic images framed through train windowpanes. Suddenly, pictures of architecture and places became another form of tourism – a window onto the world – and subsequently piqued unbridled enthusiasm for unfamiliar places.

[…]

This year, however, that is the year 2020, the year I am writing this preface and completing this manuscript, is unlike any other. This year, we are in lockdown. This year follows on the heels of 2019, a year when we were unsuspecting of the dread to come, when the coronavirus began to spread across the city of Wuhan, China, and then unexpectedly almost, while the rest of the world imagined this was not ‘our’ problem, made its way at breakneck speed to various locations across the globe until it arrived in North America in February 2020. How did it make its way? Travel. Tourism. The international connections linking one city to another, one household to another, one site to another.

This uninvited visitor, this eager speed traveller with malicious intent and endless destinations, the Novel Coronavirus, otherwise known as Covid-19, has not completed its tour of the world as I write. A pandemic that has shaken the world has enforced global health specialists to order the reverse of travel: prescribe immobility and social distancing and keep a spacing of at least two metres from others, necessarily bringing the travel industry to an abrupt halt. In attempting to confront and placate this fast-moving virus that has already targeted upwards of four million people worldwide, everyone – the entire global community – has been asked to shelter-at-home in order to be isolated from one another, one of the only reliable weapons in the international health artillery. The travel industry’s collapse was anything but gradual. It hit like a bomb: flights were brought to a standstill, all shops and commercial activities normally conducted in person were shut down, and gatherings of people were reduced from groups of 50 to 20 to none in a matter of days. Cries of devastation by the tourism sector swarm on the media unprecedentedly: tourism-dependent cities have been walloped by the crisis. For example, job losses for the Indian travel industry could be close to 38 million which accounts for approximately 70 per cent of the labour workforce. This is only one sector yet the broader landscape of travel global losses tally 75 million jobs and $2.1 trillion in revenue, in effect paralysing any thought of how travel might recover. Indeed, as National Geographic writer, Elizabeth Becker puts it, ‘The technological revolution that brought us closer together by making travel and tourism easy and affordable – a revolution that fuelled one billion trips a year – is helpless in halting a virus that demands we shelter in place.’

Forecasts of the worst economic depression to rival that of 1929 is on the horizon while unemployment is already tabulating unthinkable numbers in every country. Most of all, the lives lost to this virus so far without a vaccine or any form of inoculation shocks us all. Just as with deadly pandemics of the past, the Coronavirus continues to be responsible for ratchetting up soon to be over 500,000 fatalities, and the numbers continue to creep upward. And all the while, our worlds involute. As Paul Daley chronicles in The Guardian, ‘Our geographic orbits have shrunk. Our homes have become countries, our streets worlds and our suburbs universes. Once small things like a visit to the supermarket, a chat with a neighbour, a dog walk, hold greater emotional meaning than we’d ever have dreamt a few months back.’

And yet! While some airports are using runways as aeroplane parking lots and hotels and cruise ships are being converted into intensive care hospital wards, designers are packaging lockdown playlists, travel websites are intensifying interest in dream-worthy armchair vacations and museums are staging virtual 3D tours of exhibitions without ever having to leave home. Even the house rental giant Airbnb has introduced ‘Online Experiences’ to binge on – ‘Cultural Journey through London Chinatown’, or ‘Follow a Plague Doctor Through Prague’ – in what has been referred to as The Great Lockdown. The National Trust for Canada invites the visitor to its website with the tagline: ‘Get out your virtual passport and celebrate World Heritage Day’ on 18 April, ‘. . . a perfect moment to discover wonderful heritage places that the world has to offer’. With an offer to ‘keep your spirits high during this time of social distancing . . . From inspiring architecture to beautiful pastoral scenery, take a moment to enjoy some of Canada’s great historic places without leaving home.’

The online email newsletter, Dezeen Daily, proposes a little escapism by showcasing ten ideal remote cabins, treehouses and retreats for the readers visual delectation. The Culture Trip website invites readers to travel with them vicariously in order to ‘stay curious, dream now, plan later’ by visiting ‘. . . the New Seven Wonders of the World from Your Living Room’. And with the hope of a future Covid-19 free, are the prospective tours being advertised during the pandemic such as the ‘Great British Telly: A Tour of England’ already postponed once and rescheduled for autumn. This Public Broadcasting Station sponsored tour visits the sites and villages of some of the most popular British television series such as Midsomer Murders, Inspector Morse, Downton Abbey and more. Architectural sites include Bletchley Park, Highclere Castle and the Chavenage House where the series Poldark was filmed in part. If for nothing else and the trip is postponed again or cancelled entirely, the escapist fantasy of experiencing these virtual sites is worthwhile. A colleague, commenting on a drawing by artist, Kera Till, ‘Commuting in Corona Times’, calls it ‘fabulous and . . . relevant – how to feel a sense of movement in all this stillness and stay-at-home-ness . . . how seemingly static spaces [are] punctured by routes and pathways’.

Angkor Wat, Siem Reap, Cambodia, 2014 & Guggenheim Bilbao, by architect Frank Gehry, Bilbao, Spain, 2002. Photos by Shelley Hornstein.

So, what might all this mean for the future of architectural tourism? Perhaps the only bright spark for tourism altogether is that the extended sheltering at home imperative piques interest and fuels a desire to move, to leave the confines of isolation, and that the tangible site, the physical place, the one we cannot currently get to, will be more tantalising than ever before.

-- Extract taken from Shelley Hornstein's new book, Architectural Tourism: Site-Seeing, Itineraries and Cultural Heritage, which will be released on 20th November. Pre-order HERE.

Hardcover • 192 Pages • Size: 240 × 170 mm

25 colour illustrations and 75 B&W illustrations

ISBN: 9781848222274 • Publication: November 20, 2020

FOR MORE CONTENT ON ARCHITECTURE, ART & DESIGN CONNECT WITH US ON SOCIAL MEDIA:

https://twitter.com/LHArtBooks