Creative Legacies: Interview with Fred Noyes

Kathy Battista and Bryan Faller, editors of the recently published book, Creative Legacies, talk to Fred Noyes, Principal of Frederick Noyes Architects and son of the architect Eliot Noyes, about Noyes' New Canaan house and the challenges of preserving an architectural legacy.

(For further insight into Creative Legacies, take a look at this blogpost too!)

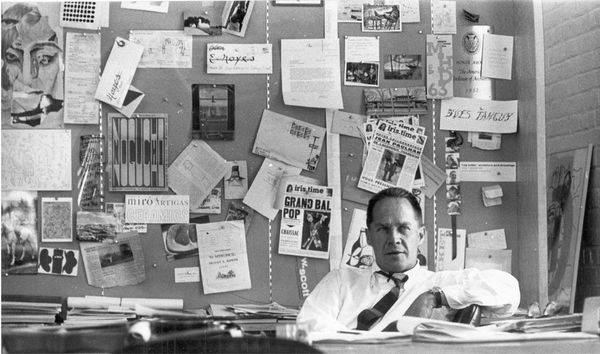

Photograph of Eliot Noyes

Photograph of Eliot NoyesQ: You and your siblings are in the process of securing your father's legacy, in particular the New Canaan House. Can you say a little about the various concerns with securing the house as a trust or foundation so that it remains intact in perpetuity?

Fred Noyes: There are many excellent houses from all eras. Which should be saved, remaining unchanged and publicly available to future generations, is a difficult decision. I believe our New Canaan house fits into that category on two counts: first, as a piece of groundbreaking architecture in its own right, and second, as a marker of my father’s broader design approach, his expansion of Bauhausian architectural design principles beyond architecture itself—specifically to Industrial Design and Corporate Design (e.g., IBM, Westinghouse, Mobil Oil).

Through Preservation Connecticut, we have already placed covenants on the house so that it will remain unchanged regardless of its ultimate use. It is not our intent, however, to make the house into a museum, a simple ode to my father. That would be static. Rather, we hope to find mechanisms to allow it the house to serve as a springboard for future generations to further develop his ideas. For instance, businesses today face different problems/opportunities than in my father’s era with his ground-breaking development of the IBM design program. His ideas need development alongside businesses as they adapt to current pressures. Design—of all stripes—should help business be consistent to themselves, a goal of making them better responsive to their clients through clear business organization and better products.

How to use the house to promote that strategy is not easy. For one, expenses of securing, operating and maintaining the house itself must be met. Second, programs, events, etc. need to be developed, maybe using the house as a core both in image and in substance, to encourage further design investigation across all disciplines. Both of these aspects will require considerable effort.

Q: I know that your father had an archive and I'm wondering if you are planning to house this at the house or to liaise with a host institution?

FN: The archives are presently in storage and in a secure facility. We consider those to be a very valuable resource to understand the fundamentals of my father’s design approach in all parts of his practice—Architecture, Industrial Design, and Corporate Consulting. Our intent is to place them where they can have maximum exposure and use. The house is not ideal for that. Several institutions are interested, but Harvard is the natural repository. There are many links: my father trained under Walter Gropius at Harvard; the Graduate School of Design established the “Eliot Noyes Chair” in his honor; and the town of New Canaan boasts the “Harvard Five,” the home of many first generation of mid-century modern architects (including non-Harvard architects).

As much of my father’s legacy was in bringing design thinking into the very organization of business practices, discussion with Harvard has focused on the archive’s joint use by both the Graduate School of Design and the Harvard Business School. It is our hope that joint programs might develop so that students in both disciples can better understand each other and work to mutual benefit when they graduate.

Q: When we met you mentioned that your mother played a significant role in the development of the house in New Canaan. Can you say more about this? Was she a trained architect as well?

FN: My mother was formally trained as an architect at the Cambridge School of Architecture in Cambridge, MA. She never officially practiced or became registered. However, she worked with my father on many projects, giving informal feedback from the other side of the table when he brought projects to work at home. Her “eye” looking at plans for what would feel good, what would be a comfortable space, what would be good lighting, etc., was terrific. Eventually she became the interiors department in his practice.

Her influence in our New Canaan house is considerable. She was always looking for features that would were both exciting and lively. The furniture, fabrics, plants and miscellaneous objects all bear her presence. She started buying bread boards—at antique stores, at swap meets, or wherever she saw them-- not for any particular artistic reason or with the idea of “collecting,” but just because she thought they were pretty. The same with early American quilts—which she bought long before they were fashionable or considered art works in themselves.

The layout of the kitchen bears her input; very practical with working counter space between the utilities, especially the long unbroken counter to allow for muss-making of large family meals. Her sense is reflected in the open overhead shelves, preferring the spark and glitter of dishes and glasses to the blandness of doors. There’s a practicality in that—no constant opening and closing of cabinet doors. All these decisions were made with my father. They worked together.

Q: Your father designed the house in the middle of a pine forest and indeed it feels shrouded by nature. Can you tell me a bit more about Eliot's interest in nature and architecture?

FN: My father’s interest was always to make whatever he was designing appropriate to the setting in which it was sitting. That applied to designing industrial design products as well as architecture.

In the New Canaan house, he was making a house to merge with the land, delighted that its mood would change with seasonal variations—as he writes in the Life Magazine article on the house in 1963. With that intent and the house sitting in a pine grove, using natural materials—stone and wood, indigenous to the Connecticut area—would have been an easy choice. So, too, was the decision on the stone wall style—large granite stones, informally stacked, mimicking the old stone walls so common in New England. More radical, perhaps, was bringing the stone walls and flagstone floors seamlessly to the interior of the house. The effect here is to minimize the interior/exterior difference, thoroughly consistent with his stated desire to integrate with nature.

Had he been designing in a different environment—say in NYC or a in desert—he would have likely used different materials, better suited to those settings. However, as there’s a warmth to natural materials—for instance wood on panels, or wool for fabrics and rugs—likely they would have found places even there. He was always looking to make spaces as comfortable and user friendly as possible, whether a house or a corporate building. User friendly also applied to his industrial design products.

Q: You have recently hosted an exhibition in the house. Can you tell me how this came about and why you and your siblings agreed to do this project?

FN: Again, as described in his statement in the Life Magazine article, the design of the New Canaan house was carefully considered to accommodate the complex, diverse and changing life typical of growing families, in this case, ours. My father considered art as simple part of that life, not necessarily something to admire in a museum. Hence the house was always filled with art, always changing and usually informally displayed—for instance pictures leaning against walls rather than hung. Art was of all styles and eras, famous artists cheek by jowl with family drawings. And always moving as new pieces were introduced.

The idea of replacing the house’s art with the exhibition art was, then, a simple extension of what the house has always been—an ever-changing receptacle for diverse images and objects. That the house so easily accommodates the present exhibit, albeit of contemporary works rather than of my father’s era, is testament to the house’s simple form, providing a strong backdrop without imposing a style or a time period for the display. The idea for the exhibit was initiated by the combined galleries and art fair. The family has been delighted to show the house’s versatility.

Photograph of Eliot Noyes

With special thanks to Fred Noyes for this interview.

Photography by Michael Biondo.

Noyes Exhibition images courtesy of the artist and: Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo; Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo/Brussels/New York; Object & Thing, New York.

Creative Legacies: Artists' Estates and Foundations, edited by Kathy Battista and Bryan Faller, is available now:

Read more about the issues and case studies covered in Creative Legacies in the editors' first blogpost HERE.