The Public and Private Lives of Keith Vaughan

In light of the recently opened Tate exhibition Queer British Art 1861–1967, author Gerard Hastings discusses the experiences of gay artist Keith Vaughan in a period before the decriminalisation of homosexuality in England.

Keith Vaughan, Nude Against a Rock, 1957, oil on board

It is very gratifying to see the work of Keith Vaughan so prominently displayed at Tate Britain’s Queer British Art exhibition. And how marvellous it looks! The challenges that such painters faced during the 1940s and ’50s were immense. Because the male nude was central to his art, Vaughan was acutely sensitive to criticism and accusation. Tragic to think that he felt he had to hide his true nature. He wrote in his journal:

December 22, 1953: I ask myself which of my pictures would I be willing to stand beside in public, say Piccadilly Circus, for all to see. The least personal ones, I suppose, abstract landscapes. The continual use of the male figure, no matter how one may develop it as a painting, retains always the stain of a homosexual conception. “K. V. paints nude young men.” Perfectly true, but I feel I must hide my head in shame. Inescapable, I suppose – social guilt of the invert.

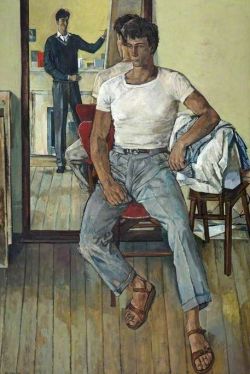

John Minton, Painter and Model, 1953, oil on canvas

Very early in his career Vaughan established a clear distinction between paintings he produced for public consumption and those he made in private for himself. He was by no means alone in manipulating his work to suit public taste. John Minton, his housemate during the late 1940s and early ’50s, also disguised a good deal of ‘queer’ imagery in his paintings, book illustrations and lithographs. For those ‘in the know’ it was obvious; the less visually literate missed the point. John Craxton’s gorgeous paintings of sleeping shepherds and dancing sailors were also infused with erotic longings, but most of his admirers in the 1950s would have missed that point.

In many of Vaughan’s paintings we sense an inclination to camouflage and conceal sexual content by means of an abstracting, formalising process. He was completely aware of what he was doing and frequently referred to facial features and genitals as ‘the attention grabbers’ since they exercised an inordinately forceful ‘pull’ on the viewer’s eye. His use of proprietous masking, disguising and filtering was not new. As with works of art from all periods, the moral attitudes and social mores of the day played their part in determining both the conception and final appearance of Vaughan’s paintings.

John Craxton, Reclining figure with asphodels 1, 1983-84, Tempera on canvas

In 1956 Vaughan was the victim of a blackmail threat owing to his sexuality. He bravely stood his ground and refused to pay, fully aware that if he was reported, he would be brought in for questioning and his premises would be searched. His first course of action was to tear out pages from his journal while enduring ‘a fear & panic which I had not known since childhood.’ He cleared away incriminating material from his flat and braced himself for the knock at the door. Much to his relief, his blackmailer did not go to the police but the ugly incident profoundly shocked him. One year later he was still suffering anxiety attacks: ‘The full horror and nightmare of his blackmailing attack suddenly became vivid again. How could I think for one moment of associating with such a person.’

Dreadful to think that gay painters suffered such torments. Congratulations to Tate Britain for telling their story.

Gerard Hastings is an artist, teacher, collector and leading expert on the work of Keith Vaughan. He is the co-author of Keith Vaughan (Lund Humphries, 2014) and the newly published Awkward Artefacts: The ‘Erotic Fantasies’ of Keith Vaughan (Pagham Press, 2017). For more information on the artist see the website of the Keith Vaughan Society (www.thekeithvaughansociety.com)