Modern Art, After Dark

Your head is coated by a thick soup of black and green paint. A roughly smeared handprint of grey-blue smoke tarnishes your jaw while sharp flecks of orange, pale yellow and white sting your cheeks and eyes. A wave of red threatens to permeate the scene as you look up, enraged, at the dandified artist standing, paint pot in hand, smirking in front of you. But then you stop, caught off guard by your reflection in a charming Godwin japonais mirror, and begin to smile. The once bland canvas of your face now displays a curious and beguiling prospect. Upon it an image vacillates between flat, tonal chords and notes of colour and the suggestion, never forced, of a landscape and night sky streaked by the sparkling tails of rockets and stars.

‘Is it. A firework display?’ you hazard.

‘Partly right’ answers Mr Whistler warmly ‘It’s a Nocturne’.

‘How very modern’ you splutter in conclusion.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket, 1875

An outrage tantamount to ‘flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face’ was John Ruskin’s verdict of James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s 1875 painting Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket. The eminent critic mustered and voiced an entire Victorian generation’s shock at the sudden breakdown of traditional pictorial values. What Ruskin’s theatrically exaggerated barb and the infamous libel case that resulted from it overshadow however, is the painting’s heralding of modernist visual sensibilities in a hitherto sheltered British art world and the introduction of the nocturne as one of the defining tropes of modern British art.

The black expanse of the night sky that both invites and repudiates the gaze was the perfect site from which to commence more modernist, ambiguous and exciting relationships between image and surface. Light is the fundamental element in the operation of sight and in Whistler’s mind, the nocturne – refusing the easy light and colour of day – allowed for a painting more akin to music ‘divesting the picture of any outside anecdotal interest’. ‘A nocturne’ said Whistler ‘is an arrangement of line, form and colour first’.

Whistler’s pupil Walter Sickert carried his discoveries forward to subsequent generations of twentieth century artists. Sickert’s night scenes were less often painted in the open air, than in the dark recesses of the music hall and theatre, where apparitions of performers scorched by flat yellow lamplight, haunt the bitumen-blackened canvas.

Walter Richard Sickert, Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford, 1892

Even in the searing light of southern Europe, Modern British artists such as Sickert or later Carel Weight seem to rush for darker corners. Sickert wipes and prods and pokes at the facades and columns of Venetian palaces, determined to show that grime and shadow and an indistinction of colour can play perhaps a more honest role in communicating the modern visual aspect of a place.

The unusually clear light of St Ives holds a blinding and disproportionate claim to the soul of modern British art. A purer, supposedly more continental abstraction was, it seems, a more natural discovery under the sunshine of the Cornish coast, as evidenced in works such as Nicholson’s White Reliefs, Patrick Heron’s Garden paintings or Peter Lanyon’s Glider series. But beyond this gentile retreat, artists throughout the rest of the country continued to make some of their most important discoveries after the sun had set. Bomb damaged buildings by John Piper, intriguing still-lives by Mary Fedden and crucifixions by Craigie Aitchison all use the muted colours of night as an excuse to flatten images and explore interesting amalgams of shape and tone.

One of the finest contemporary proponents of this British artistic nyctophilia is Tom Hammick. Far too mild mannered as to throw his paints in your face, Hammick would be more likely to lay you down gently and roll colour directly over you, taking great care to ensure the infiltration of pigment around the protuberance of your nose and indents of your eye sockets. For contemporary viewers though, or at least those less prone to bouts of late-Ruskinian visual indignation, the nocturne’s effect remains the same. In the indistinct light of evening and night, the picture plane is flattened allowing more formal qualities to assert themselves.

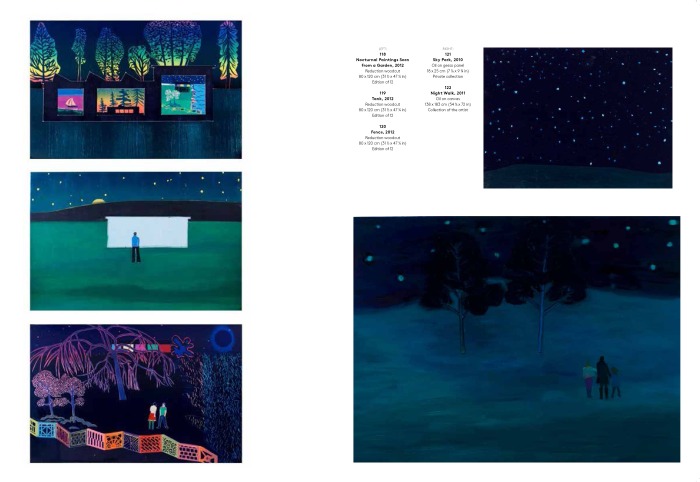

Two works, Edgeland, 2011 and Moonlit Woods, 2012 share a favourite motif of Hammick’s. A mother and daughter stand in a nocturnal landscape, holding hands with backs turned to the viewer, looking out to some as yet unclear vista. This cue asks the viewer to join their gaze, to search for a distance that the dim colour and lack of clear light seem determined to refuse. In Moonlit Woods, the dark ground, dusky blue sky and trees are thoroughly compacted; the bare ladder-like branches of the trees suggest and permit a movement of the eye up and down the canvas, but by the same token bar the way in and onward.

Tom Hammick, Moonlit Woods, Oil on Canvas, 2012

In a description of which Whistler would surely approve, Julian Bell says of Hammick’s night scenes:

‘Like a musician striking up in a minor key, Hammick plunges […] into a plangent ambience of blue. Late evening going on deep night takes over as the default condition for his art after his move to the country, both colouristically and literally: work on the pictures gets pushed into strange places by small-hours rhythms and reveries.’

The ‘strange places’ Bell describes lie beyond the picture’s surface: those representational and romantic qualities of the night scene that – despite Whistler’s insistence on formal primacy – always re-emerge in the process of viewing. A romantic impulse runs through much of modern British art and in the works of artists such as John Craxton, Graham Sutherland, Paul Nash and latterly Tom Hammick, is at its most heightened in scenes painted at night.

Tom Hammick, Edgeland, Edition Variable Reduction Woodcut, 2011

In Edgeland, a woodcut, the flattening of elements is even more severe. The figures of mother and daughter are present, but night sky and ground on which they stand are reduced to their barest visual necessities: a band of black and red. The viewer of Hammick’s work will inevitably question the motives of the figures, walking in a bleak landscape of strange colours, immersed in the same uncanny ‘semi-obscurity’ that Paul Nash identifies in his 1913 pen and wash drawing Cliff to the North, or wonder what it is they look towards.

Paul Nash, The Cliff to the North, 1913

Hammick’s imprint of wood grain onto the surface of the print, like a plywood barricade suddenly slapped in front of the eyes, feels a last ditch, knowingly tongue in cheek attempt to hold the viewer’s attention at surface level. The artist knows all too well that perception will yo-yo between surface and representation; qualities of paint on support and object of representation. At either end of the string, his work stands in a fine lineage of modern British nocturnal painting.

Tom Furness, Publishing Assistant, Lund Humphries

The exhibition Tom Hammick: Wall, Window, World is at Flowers Gallery, London until 10 October, 2015. Julian Bell’s book of the same name is published by Lund Humphries. A special edition, incorporating the three-part colour etching Fallout is also available.