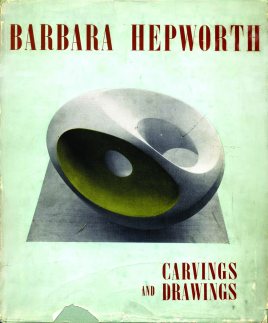

Lund Humphries Landmarks – Barbara Hepworth: Carvings and Drawings, with an Introduction by Herbert Read (1952)

Frances Guy considers the contributions of Barbara Hepworth and Herbert Read to a book which helped to establish Hepworth’s reputation as a key British artist.

This was the first major monograph to be published on Barbara Hepworth, at the start of a decade which saw her career develop on the international stage and her sculpture become even better known through public commissions. In 1950, Hepworth represented Britain at the 25th Venice Biennale and a year later her first public sculptures, Contrapuntal Forms and Turning Forms, were displayed on London’s South Bank as part of the Festival of Britain. In 1951, she designed the sets and costumes for Electra at the Old Vic and a retrospective of her work was held in her place of birth in Wakefield. It was also the year that her marriage to Ben Nicholson finally came to an end − perhaps even more reason to take the opportunity to clearly state her purpose and lay claim to her position as one of Britain’s most innovative artists.

Herbert Read wrote the foreword to Hepworth’s exhibition with Nicholson in 1932 and, as a long-time supporter of her work, it was appropriate that he should also write the introduction to Carvings and Drawings. In 1944, he had done the same for Henry Moore in the Lund Humphries book Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings. It is significant to note the difference in the titles: for Hepworth, ‘direct carving’ was by far the most important of her artistic principles. Read drew parallels between the two artists in his introduction to Hepworth’s book, perhaps giving credence to the notion that her work had to be understood in reference to that of Moore. But he also attempted to highlight the differences in their practice, albeit with reference to their gender, identifying Hepworth’s search for beauty and mystery in opposition to Moore’s concern with vitality and power. Interestingly, given the context, Read also chose to question whether Hepworth’s quest for a ‘new reality’ would be successful and criticised her for what he saw as an ‘unhappy compromise’ in her work by incising naturalistic motifs on otherwise abstract forms. In this, he found her commitment to abstraction fell short in comparison to that of Naum Gabo, another of her contemporaries.

Read also stated how Hepworth had ‘traced her own development as an artist with an incomparable subtlety and self-understanding, and thereby relieved me of a necessary but difficult task’. Indeed, Hepworth had written statements about her practice since the early 1930s, published in the journals of Unit One, Circle and Studio magazine. The six texts she wrote for Carvings and Drawings develop this dialogue, reflecting on key moments and influences that contributed to the development of her practice and artistic sensibilities but also alluding to a more fundamental consideration of the role of the artist in society. They are illustrated with her own photographs, including some of early sculptures, such as the iconic first Pierced Form of 1931, which were destroyed during the Blitz or which have otherwise been lost.

Barbara Hepworth, Pierced Form, Pink alabaster, 1932, destroyed in war, Copyright Hepworth Estate

In these texts she divided her career into six chronological sections, tracing her earliest encounters with art in the classrooms at Wakefield Girls High School and memories of the Yorkshire landscape, to her meetings with Brancusi, Braque, Mondrian, Picasso and other members of the European avant-garde in the 1930s, and her most recent experiences observing people gathering in the Piazza San Marco in Venice and the sense of community that came with the Festival of Britain. The texts also outline Hepworth’s most vital concerns: the idea of the ‘figure in the landscape, the ‘fundamental and ideal unity of man with nature which I consider to be one of the basic impulses of sculpture’; and her commitment to abstraction, ‘a new approach which would allow me to build my own sculptural anatomy dictated only by my poetic demands from the material’. She also underlined the importance of drawing at different stages in her career, helping her to develop ideas for her sculptural practice.

Hepworth also cited the influence of her day-to-day life and interests: her home, her children, music and dancing. In doing so, she echoes Read’s statement that ‘she has remained a completely human person, not sacrificing either her social or her domestic instincts, her feminine graces or sympathies, to some hard notion of a career’. However, crucially, Hepworth identifies this feminine experience as complementary to, rather than competing with, its masculine counterpart, and her sense of form as a physical response born of her experience as a woman: ‘it is a form of being rather than observing, which in sculpture should provide its own emotional and logical development of form’.

Carvings and Drawings represented a significant development in the appreciation of Hepworth’s work at a critical moment in her career, and undoubtedly contributed to the growing recognition of her status in the history of Modern British art.

Frances Guy

Frances Guy is Head of Collection & Exhibitions at The Hepworth Wakefield. She worked closely with Dr Sophie Bowness, Hepworth’s grand-daughter, on the installation of the Hepworth Family Gift, a unique collection of Hepworth’s working models at the heart of the new gallery. She has written essays about Hepworth for Barbara Hepworth: The Plasters (Lund Humphries, 2011) and Barbara Hepworth: The Hospital Drawings (2012). Previously she led the curatorial department at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, curating numerous exhibitions of Modern British art and the gallery’s first international exhibition, Eye-Music: Kandinsky, Klee and all that Jazz (2007).